Catherine Ellis

Journalist

Medellín report, Colombagonzalo Rojas

A young Gonzalo Rojas and his father, who was killed by Pablo Escobar

A law proposed at the Colombia Congress seeks to prohibit the sale of goods which celebrates the former drug lord Pablo Escobar. But opinions are divided there.

Monday, November 27, 1989, Gonzalo Rojas was at school in the Colombian capital of Bogota when a teacher came out of the class to provide devastating news.

His father, also called Gonzalo, died in a plane crash that morning.

“I remember leaving and saw my mother and grandmother awaiting me, crying,” said Rojas, who was only 10 years old at the time. “It was a very, very sad day.”

A few minutes after takeoff, an explosion aboard the Avianca flight 203 killed the 107 passengers and the crew, as well as three people on the ground that were affected by falling debris.

The explosion was not an accident. It was a deliberate bomb attack by Pablo Escobar and his Medellín cartel.

While a time defined by drug wars, bombing, kidnappings and a sky murder rate has been largely relegated to the past of Colombia, Escobar’s heritage was not.

The criminal notorious, which was killed by the security forces in 1993, obtained an almost cult status in the world, immortalized in books, music and television such as the Netflix Narcos series.

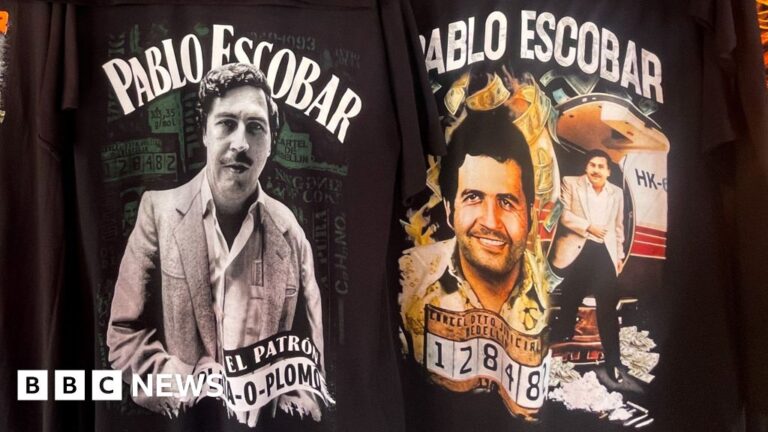

In Colombia herself, her name and her face are adorned with cups, keys and t-shirts in tourist stores which are mainly aimed at curious visitors.

But a law proposed at the Colombia Congress seeks to change this.

The bill wants to ban Escobar goods – and that of other convicted criminals – to help put an end to the glorification of a drug boss who was central to the world trade in cocaine and largely held responsible for at least 4,000 murders.

“The difficult problems that are part of the history and memory of our country cannot simply be recalled by a t-shirt or a sticker sold to a street corner,” explains Juan Sebastián Gómez, member of the Congress and Co -Ator of the bill.

The proposed law prohibits the sale, as well as the use and transport of clothing and articles promoting criminals, including Escobar. This would mean fines for those who have violated the rules and a temporary suspension of companies.

Catherine Ellis

The memories of Pablo Escobar are widely available in Colombia

Many sellers who sell goods claim that a law prohibiting this commodity would affect their livelihoods.

“It’s terrible. We have the right to work, and these Pablo t-shirts are sold particularly well,” explains Joana Montoya, who has a stand filled with Escobar goods in Comuna 13, a popular tourist area of Medellín.

Medellín, the hometown of Escobar, was known as “the most dangerous city in the world” in the late 1980s and in the early 90s due to violence associated with drug wars and armed conflict of the Colombia.

Today, it has been revitalized in a hub of innovation and tourism, with sellers wishing to enjoy the influx of visitors who wish to bring back to the House of Souvenirs – some linked to Escobar.

“This Escobar commodity benefits many families here – it supports us. It helps us pay our rent, buying food, taking care of our children,” explains Ms. Montaya, who supports herself and her young girl.

Ms. Montoya says that at least 15% of her sales come from Escobar products, but some sellers tell the BBC that for them, it’s up to 60%.

Catherine Ellis

Stall holder Joana Montoya says that the memories of Pablo Escobar provide him with a vital income

If the bill is approved, there would be a defined period for sellers to familiarize themselves with the new rules and eliminate their Escobar stock.

“We would need a transition phase so that people can stop selling these products and replace them with others,” said the Gómez Congress member. He says that Colombia has more interesting things to show that the drug lords and that the association with Escobar stigmatized the country abroad.

Some of the t -shirts, sold for about £ 5, wear a slogan linked to Escobar – “Silver or Lead?”. This symbolizes the choice that the owner of the cartel gave to those who have constituted a threat to his criminal operations: to accept a bridge pot or be killed.

The María Suarez store assistant believes that the profit from sales of ESCOBAR goods is not ethical.

“We need this ban. He has done horrible things and these memories are things that should not exist,” she said, explaining that she feels uncomfortable that her boss stores Escobar articles.

Escobar and its Medellín cartel at some point would have checked 80% of the cocaine entering into the United States. In 1987, he was appointed as one of the richest people in the world by Forbes magazine.

He spent part of his fortune to develop private neighborhoods, but many people consider this to be a tactic to buy loyalty in certain population segments.

Years after the death of his father, Mr. Rojas remembers him as a calm and responsible man, who loved his family. For him, the bill is a decisive moment.

“This is an important step on the road to the way we think about what is happening in terms of marketing the images of Pablo Escobar in order to correct it,” explains Mr. Rojas.

However, he has criticism of proposals. He thinks that the bill does not focus enough on education.

Juan Sebastián Gómez

The member of the Congress Juan Sebastián Gómez says the accent on the reputation of Escobar Harm Colombia

Mr. Rojas remembers several years ago when he met a man wearing a green t-shirt with an Escobar silhouette, and the words “Pablo, president”.

“It caused me such confusion that I couldn’t tell him anything,” he said.

“There must be more emphasis on how we deliver different messages to new generations, so that there is no positive image of what a cartel boss is.”

Mr. Rojas was actively involved in efforts to reshape the stories around Escobar and the drug trade. With other victims, he launched Narcostore.com in 2019, an online store that seems to sell items on the theme of Escobar.

But none of the products really exist and when customers select an article, they are displayed a video testimony of a victim. Mr. Rojas says that the site has attracted 180 million visits from around the world.

In Colombia, Congress, the bill faces four stages which it must adopt before it can become law. Gómez says that he hopes that it arouses reflection inside and outside the congress.

“In Germany, you do not sell Hitler T-shirts or Swastikas Cross. In Italy, you do not sell Mussolini stickers, and you are not going to Chile and do not get a copy of the card of Identity of Pinochet.

“I think the most important thing that the bill can make is to generate a conversation as a country – a conversation that has not yet occurred.”

The mayor of Medellín – who was also a presidential candidate in the 2022 elections – publicly supported the bill, calling the commodity “an insult to the city, the country and the victims”.

In El Poblado, a high -end area of popular Medellín with tourists, three Americans travel a stand overwhelming with memories. We buy a cap with the name and face of Escobar printed on the front. He says he wants a memory of “history”.

But for the supporters of the bill, it is not a question of withdrawing Escobar from history, it is a question of erasing a mythical construction of him, of promoting new ways of honoring the victims he has killed – and to recognize the persistent pain of the victims left behind.