BBC

Michael Northey's father was one of four soldiers killed in the Korean War who were successfully identified.

From his wheelchair, Michael Northey quietly watches over his father's grave and lays a flower for the very first time.

“I’ve never been this close to him in 70 years, which is ridiculous,” he jokes poignantly.

Born into a poor family in the backstreets of Portsmouth, Michael was still a baby when his father, the youngest of 13 children, went off to fight in the Korean War. He was killed in action and his body has never been identified.

For decades he lay in an unmarked grave at the United Nations Cemetery in Busan, on Korea's southern coast, adorned with the plaque “Member of the British Army, Known to God.”

It now bears his name: Sergeant D. Northey, who died on April 24, 1951, at the age of 23.

Sergeant Northey, along with three others, are the first unknown British soldiers killed in the Korean War to be successfully identified, and Michael attends a ceremony, along with the other families, to rename their graves.

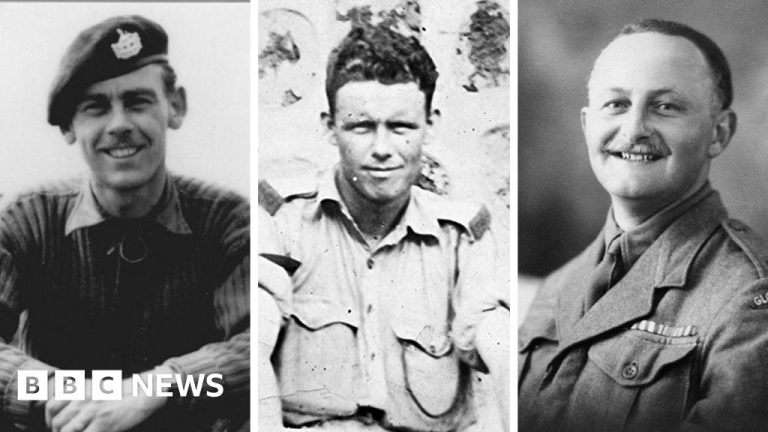

Sergeant D. Northey, Corporal William Adair and Major Patrick Angier were killed in action during the Korean War.

Michael had spent years doing his own research, hoping to discover his father's whereabouts, but he had ultimately given up.

“I'm sick and I don't have much time left, so I had written it off, I thought I'd never know,” he said.

But a few months ago, Michael received a phone call. Unbeknownst to him, Department of Defense researchers were conducting their own investigation. When he heard the news, he said he “cried like a banshee for 20 minutes.”

“I can’t describe the emotional release,” he says, smiling. “It haunted me for 70 years. The poor lady who called me, I felt sorry for her.

Michael Northey

Michael was a baby when his father went to fight in the Korean War.

The woman on the other end of the line was Nicola Nash, a forensic researcher at the Joint Casualty and Compassionate Center in Gloucester, who usually works on identifying victims of the First and Second World Wars.

Tasked for the first time with finding the dead of the Korean War, she had to start from scratch by first drawing up a list of the 300 British soldiers still missing, including 76 buried in the Busan cemetery.

Nicola looked through their burial records and discovered that only one man had been buried wearing the stripes of a sergeant of the Gloucester Regiment, as well as a major.

After scouring the national archives and cross-referencing eyewitness accounts, family letters and war office reports, Ms. Nash was able to identify these men as Sergeant Northey and Major Patrick Angier.

The men were in unmarked graves, but their graves have now been renamed.

Both were killed in the famous Battle of the Imjin River in April 1951, as the Chinese army, which had joined the war on the side of North Korea, attempted to push Allied forces down the peninsula to retake the capital Seoul. Despite being outnumbered, the men held their position for three days, giving their comrades ample time to retreat and successfully defend the city.

The problem at the time, Ms. Nash said, was that because the battle was so bloody, most of the men were killed or captured, leaving no one to identify them. The enemy had removed and scattered his identity tags. Only after the POWs were released were they able to share their stories, and no one had thought to go back and piece together the puzzles – until now.

For Ms Nash, it has been a six-year “labor of love”, made slightly easier, she admits, by being able to rely on some of the men's children still alive, which also made the more special process.

“Children have gone their whole lives not knowing what happened to their fathers, and for me to be able to do this work and bring them here to their graves and say goodbye and bring closure to this story means everything.” , she said.

Major Angier's daughter, Tabby, had already visited the cemetery without knowing that her father was buried there.

At the ceremony, families sit in chairs amid long rows of small stone tombs, commemorating the thousands of foreign soldiers who fought and died in the Korean War. They are accompanied by serving soldiers from their loved ones' former regiments.

Major Angier's daughter, Tabby, now 77, and her grandson Guy, stand up to read extracts from letters he wrote from the front. In one of his last speeches, he said to his wife: “Much love to our dear children. Tell them how much Dad misses them and that he’ll be back as soon as he’s finished his work.”

Tabby was three years old when her father went to war, and her memories of him are shattered. “I remember someone standing in a room and canvas bags piling up, which must have been his equipment to go to Korea, but I can't see his face,” she said.

At the time of her father's death, people didn't like to talk about war, Tabby said. Instead, the people of his little village in Gloucestershire used to say: “Oh, those poor children, they've lost their father.” »

“I used to think that if he got lost, they would find him,” Tabby said.

But as the years passed and she learned what had happened, Tabby learned that her father's body would never be found. The last recorded trace was that he had been left under an overturned boat on the battlefield.

Tabby has already visited this cemetery twice, in an attempt to get as close to her father as possible, without knowing that he was there the whole time. “I think it will take some time to understand,” she said from her newly decorated grave.

Cameron Adair's great-granduncle, Corporal William Adair, was one of the four soldiers identified.

The shock was even greater for Cameron Adair, 25, from Scunthorpe, whose great-uncle, Corporal William Adair, is one of two Royal Ulster Rifles soldiers Ms Nash also managed to identify. The other is Rifleman Mark Foster from County Durham.

Both men were killed in January 1951 when they were forced to retreat by a wave of Chinese soldiers. Corporal Adair had no children and when his wife died, his memory also faded, leaving Cameron and his family unaware of his existence.

Discovering that his loved one “helped bring freedom to so many people” brought Cameron “a real sense of pride,” he said. “Coming here and witnessing this really brought it home to me.”

Now the same age as his uncle was when he was killed, Cameron feels inspired and says he would like to serve if the need ever arises.

Ms Nash is currently collecting DNA samples from relatives of the other 300 missing soldiers, hoping she can give more families the same peace and joy she brought to Cameron, Tabby and Michael.

“If there are still any British staff missing, we will continue to try to find them,” she said.